How do you feel about your handwriting? Did you imitate the elegant cursive script of a school-mate you slightly fancied? Do you hide your ballooning Bs and hearted-topped Is from prospective friends and employers? Chances are you don’t give it much thought anymore. With the advent of keyboards so small you can carry one in your pocket, we write everything from love letters to shopping lists as emails, texts or tweets. We choose the path of greatest ease. I often use a Moleskine App on my smartphone while a Moleskine notebook languishes at the bottom of my satchel – which is just about as vain as it is bizarre.

And yet there is good reason, argues Philip Hensher, for such a paradoxical evaluation of our handwritten style: “We have surrendered our handwriting for something more mechanical, less distinctively human, less telling about ourselves and less present in our moments of the highest happiness and the deepest emotion,” he writes, while simultaneously recognising that “if someone we knew died, I think most of us would still write our letters of condolences on paper, with a pen.”

Hensher’s new book The Missing Ink: The Lost Art of Handwriting (And Why it Still Matters), rests on the argument that “ink runs in our veins, and tells the world what we are like”. Handwriting “registers our individuality, and the mark which our culture has made on us. It has been seen as the unknowing key to our souls and our innermost nature. It has been regarded as a sign of our health as a society, of our intelligence, and as an object of simplicity, grace, fantasy and beauty in its own right.”

The Observer published an extract from the book last weekend, in which Hensher cited a number of examples from the not-so-distant past when an individual’s hand was considered an irrefutable indicator of their personal traits, and one of inestimable importance. “In 1847, in an American case, a witness testified without hesitation that a signature was genuine, though he had not seen an example of the handwriting for 63 years: the court accepted his testimony.” Hensher continues, “American Demographics claimed that bad handwriting skills were costing American business $200m in 1994”, and recalls the cases of Moira Pullar and Gordon Brown’s letter of condolence, in which bad handwriting caused enormous grief.

We ridicule illegibility in our handwriting above all. It is the source of that aphoristic slice of conventional wisdom with which all are familiar (especially Larry David): if you want to read a doctor’s note, take it to a pharmacist. Resisting accusations of ludditism, Hensher in no way advocates we try to slow the advance of keyboard-led communication by refusing to accept it. It’s quick, it’s universal and it works. Instead, his book reminds us of the joy of writing by hand: its mysterious power, its physicality and reflexiveness, likening the pleasures it produces to those of cooking a meal from scratch, or talking an unhurried walk in the sun. These are activities technology has surpassed (think microwaves, cars), yet which continue to produce enjoyments that are unsurpassable. “Sometimes,” Hensher observes, “we don’t spend an evening watching Kim Kardashian falling over on YouTube: we read a book”.

You may recall TV dramas in which the forensic assessment of a suspects’ jagged script enables the just prosecution of a lucid murder rather than an innocent (but pathological). Throughout the 20th century the science of graphology gained traction, crystallising a series of psychological traits detected in the size, layout, slant, connectedness, speed, regularity, letter forms and angularity of a person’s writing, something which fuelled widespread speculation about Hitler’s scrawl, a subject to which Hensher dedicates a short paragraph in the book. In 1942 Time argued, “If taken away from fortune-tellers and given serious study, graphology may yet become a useful handmaiden of psychology, possible revealing important traits, attitudes, values of the ‘hidden’ personality.”

Richard Wiseman, a professor of public understanding has stated explicitly “There is no credible scientific evidence with it at all. Every controlled test has showed that no evidence has emerged”. Hensher too disregards the idea that a sharp slant and thin lower loops might indicate genocidal tendencies (though cf. Caroline Crampton, very suspicious) he is not so willing to believe that the way we make sense with pen and paper has nothing more to tell us.

Some people, when giving a book as a gift, write a personal message on the inside cover. Others insist on continuing the outmoded tradition of sending laughably ugly postcards home from far flung destinations and some even maintain epistolary relations with one or two distant friends. I am one such fossil. Why should we consider quirky or attention-seeking acts which all of fifteen years ago were ubiquitous and everyday, part of the fabric of our lives? We do this because, as Hensher argues, “it has so much of you in it”, and because of what is signified by the act: this matters, it will last a little longer than most of the things we say to one another. Perhaps, I enjoyed doing this for you.

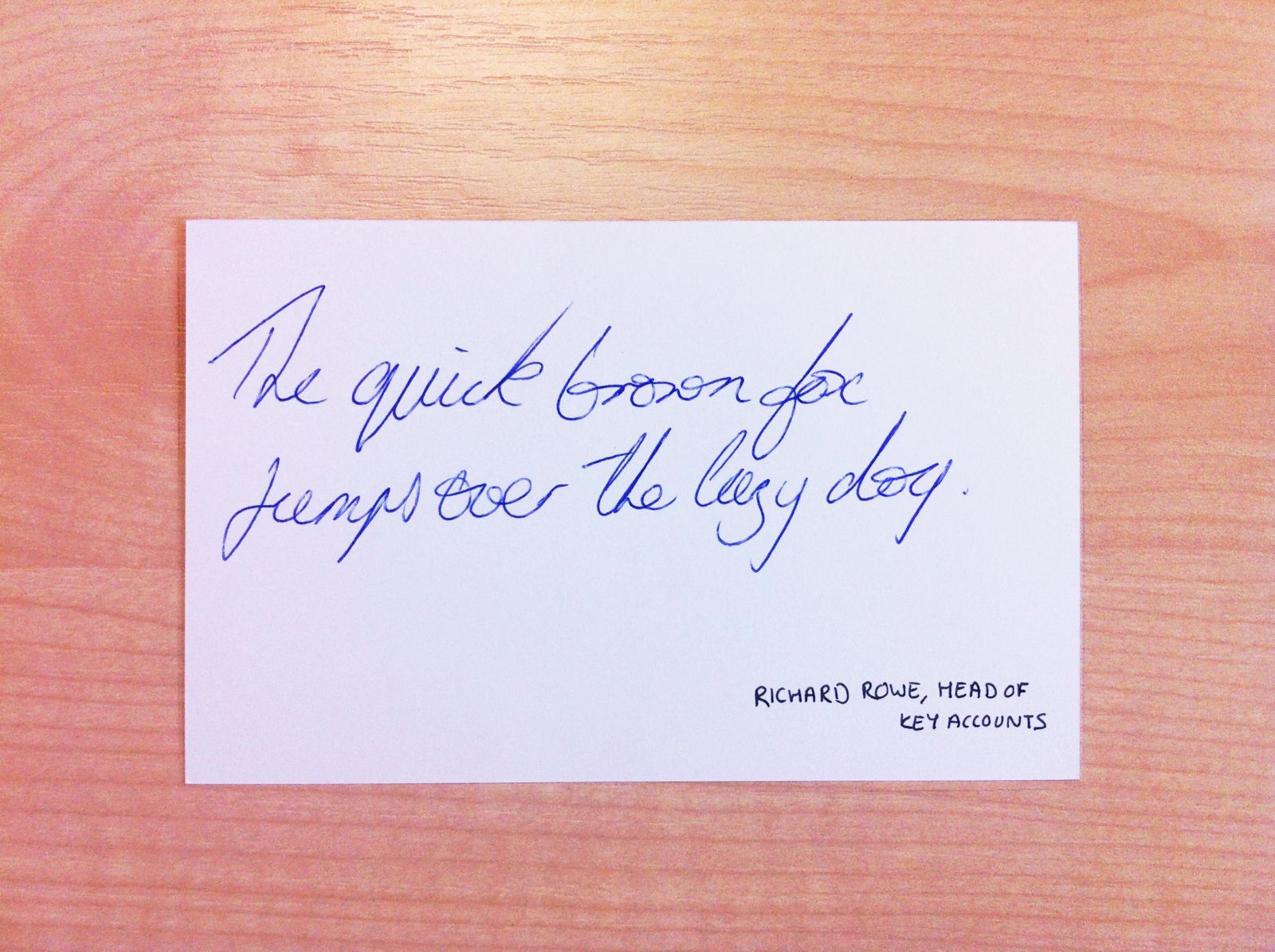

In order to test some of Hensher’s theories, this morning I conducted a pseudo-scientific study, using the subjects most readily available to me – staff in the New Statesman office. I had them write out the famous pangram: “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog” (a pangram is a sentence which uses every letter of the alphabet. A perfect pangram does so without repetition, as in “TV quiz jock, Mr PhD, bags few lynx”), to see whether any notable difference emerged between each role, to search for any tell-tale signs of impending fascist megalomania, or discernible differences between culture, design, ads and politics. What emerged was a room full of sheepish journalists, forced to acknowledge the fact that showing off your handwriting means revealing a little piece of yourself.

And finally, in the interest of full disclosure, the blogger:

Look at that “Z”. A lunatic if ever there was one.

The Missing Ink by Philip Hensher is published tomorrow by MacMillan.