In 2011, a year after David Cameron became prime minister, his government released its Pandemic Preparedness Strategy. The World Health Organisation (WHO) praised the plan, stating that the UK “remains amongst the leaders worldwide in preparing for a pandemic”.

Yet a year earlier, the new Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition had embarked upon a policy that would undo all this good work in the period of a decade – and lead to the UK’s response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic being ranked as among the worst of the world’s richest nations.

Austerity, a programme of deep public spending cuts intended to reduce the annual budget deficit and shrink national debt as a percentage of GDP, has defined Britain’s lack of resilience against Covid-19. The cuts were almost perfectly tailored to weaken the state and the public realm.

The three publicly funded frontiers of Britain’s struggle against coronavirus – health, education and community services – were only just emerging bruised and diminished from a ten-year assault on their resources. A public sector pay freeze, imposed by the then chancellor George Osborne’s emergency Budget of 2010, meant that wages had stagnated in real terms for many of the key workers we were relying on during the crisis.

Health and care workers have had a particularly tough decade. Government spending on health has risen at a slower rate than it did during the preceding decade over the past ten years, leading to operations being cancelled more frequently (there was a 14 per cent rise in cancellations from 2009 to January-March 2020), and available overnight hospital beds falling by 11 per cent in the same period.

Although the number of adult critical care beds rose in England by 776 between August 2010 and February 2020, pressure on hospitals had been increasing: every major accident and emergency unit in England failed its four-hour waiting time target for the first time in November 2019.

As isolation and boredom during lockdown exacerbate mental illness and addiction, mental health services are stretched. Between 40 and 50 per cent of mental health trusts in England saw budget reductions each year between 2012 and 2016. Waiting times for therapy on the NHS have been rising: last year one in six waited longer than 90 days for their first proper session after their initial assessment.

Schools, too, have taken a hit that has weakened their Covid-19 response – from playground sell-offs, growing classroom sizes and equipment shortages to recruitment crises, teaching assistant redundancies and the loss of special educational needs staff. The number of students in classes of more than 30 has risen over the past decade, making social distancing in classrooms even harder. The percentage of secondary school pupils in a class of over 30 has risen from 10.4 per cent in 2009 to 13 per cent in 2019.

Cuts to benefits have left a tattered safety net for the millions who have lost their livelihoods during the pandemic. The number of people claiming work-related benefits since March has increased by 125.9 per cent.

More than £30bn has been erased from the welfare budget by the coalition and successive governments since 2010, enshrined in the new system of Universal Credit. Among this notorious scheme’s many flaws is its design to delay a claimant’s first payment by five weeks – which can leave people diagnosed with Covid-19 penniless as they are expected to stop work and self-isolate immediately upon infection.

This five-week wait has been the main driver of rising food bank use in recent years. There was a 3,772 per cent rise in the number of food parcels provided by food banks between 2009 and 2019. This doesn’t account for the spike in food-bank use during the pandemic: April 2020 was the busiest month ever for UK food banks, with an 89 per cent rise in demand on the same period of last year.

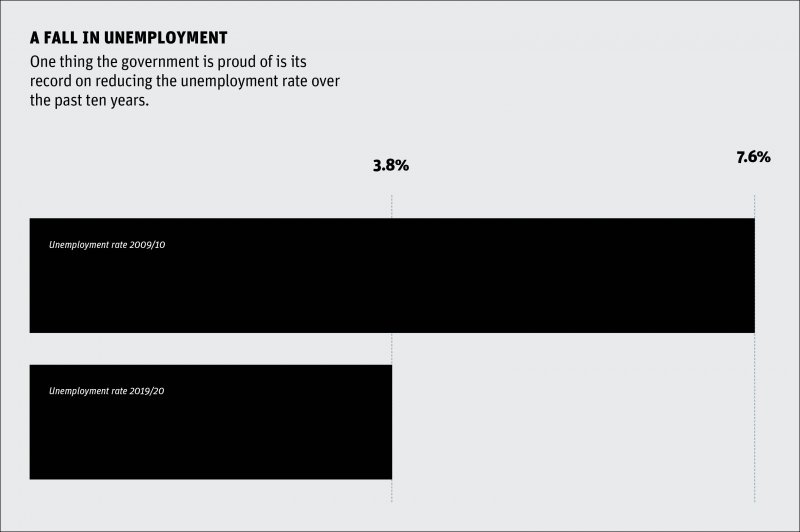

Child poverty has been rising over the past two years, with 30 per cent of children identified as living in poverty in 2018-19. Two-thirds of these children are from a household where at least one parent is in work. Over this period, the country was experiencing a so-called jobs miracle, but low levels of unemployment disguised a workforce addled with bogus self-employment, gig economy precarity and casual contracts. One in eight workers now live below the poverty line and struggle to make ends meet.

Not only does such widespread poverty put a strain on our public services, it damages people’s health too. An update of the 2010 Marmot Review into health inequalities published in February this year blamed austerity for stalling increases in life expectancy for the first time in a century. It also found health inequalities had widened in the ten years since the original report.

Indeed, there is now a greater prevalence of diabetes and obesity among the general population – both of which have been linked in early studies to a heightened risk of death when hospitalised with Covid-19. Diabetes prevalence in English GP patients aged 17 and above rose from 5.30 per cent in 2009-10 to 6.93 per cent in 2018-19. Obesity prevalence in English patients aged 16 and above has risen from 9.03 per cent in 2014-15 to 10.12 per cent in 2018-19.

Although the government successfully scaled up hospital capacity for Covid-19 patients, the rest of the health and social care system has been degraded to the point where it will struggle to catch up on the cancelled operations and delayed referrals of non-Covid-19 patients.

Most insidious, however, is the way cuts to local authority budgets from central government quietly weakened everyday services. In 2020, councils had lost an average of 60p in every pound of their government grants since 2010. Library closures, potholes and overspilling bins were a visible sign of crumbling local services, but only now is the damage to social care and public health obvious to all. While real-terms reserves for public health spending grew between 2012 and 2015 as councils took over responsibility for public health, they have since fallen – by 30 per cent from 2015 to 2019.

Social care services, also run by councils, have suffered. The average council spend on adult social care per person fell 9 per cent in real terms from 2010 to 2019. Councils have a legal duty to provide social care, so are forced to cut other, non-statutory services simply to keep up with the rising cost of an ageing population. Public parks and green spaces, crucial for exercising, well-being and meeting with friends and family during the pandemic, have also had resources cut. Council spending on environmental services per capita fell in real terms by 25 per cent from 2010 to 2019.

More than 12,000 public spaces have been sold off by councils desperate for cash since 2014-15, according to an investigation by the Bureau for Investigative Journalism and HuffPost in March 2019, including libraries, community centres and playgrounds. With the population rising, and the constant pressures of commercial and residential development, the number of people living further than a ten-minute walk from a public park is expected to rise by 5 per cent over the next five years, according to analysis by the Fields In Trust charity.

It seems as if the collateral damage of lockdown has fallen mostly on councils. They are required, for example, to house rough sleepers, when austerity has led to the number of homeless households rising by 74 per cent from 2010 to 2019. They must protect victims of domestic abuse – incidents of which have shot up with families stuck indoors – when 9 per cent of women’s refuges in England closed between 2010 and 2018.

The burden of austerity has always been shouldered by society’s poorest and vulnerable: those who rely the most on state services. Private affluence, as the economist JK Galbraith identified, coexists with public squalor. Coronavirus and the ensuing lockdown, however, have exposed for all to see the deep, self-inflicted fractures in our national and local infrastructure.

Breaking with the legacy of his predecessor and fellow old Etonian David Cameron, Boris Johnson has promised that the government’s plan for a post-pandemic economic recovery will not mean more austerity. But as councils across Britain face black holes in their budgets and teeter on the edge of bankruptcy – as the New Statesman revealed in a report on 10 June – the much-hailed “end of austerity” is yet to begin.

Read more from this week’s special issue: “Anatomy of a Crisis: How the government failed us over coronavirus”

This article appears in the 01 Jul 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Anatomy of a crisis