The failure of the professional polling industry to predict the outcome of this general election has been well documented, and has no doubt prompted a great deal of soul-searching. What has received less attention, however, is that for those hoping social media can be used to predict election results, there has been similar disappointment.

Social media has its challenges as a predictor – for example, it is no secret that Twitter users are disproportionately young and well educated, automatically skewing any analysis. However, students of the 2009 German federal elections found a surprising number of correlations, including between the number of times parties were mentioned on Twitter and the share of the vote those parties received.

In this election, a team of academics from the Information Technology Institute, the University of Warwick and City University London hoped to repeat the trick by combining social media analysis with conventional polling data. During the 2014 EU election and 2015 Greek election, this approach had brought some success – for Greece, they delivered a better prediction than all 31 of the conventional polls leading up to voting day.

Yet there was to be disappointment when they turned their methodology to #ge2015. Finding themselves in similar territory to the pollsters, they ended up giving 34% of the vote to Labour and 33% to the Conservatives. Even their confidence interval ranges were outside the final result.

But while social media can’t always predict the future, it nevertheless played an important role in this election. Facebook in particular was a competitive battleground for the main parties, with the Conservative Party reportedly spending more than £100,000 a month on this channel. It was rewarded for this investment with 514,000 “likes”, well ahead of UKIP with 477,000 and Labour with 329,000.

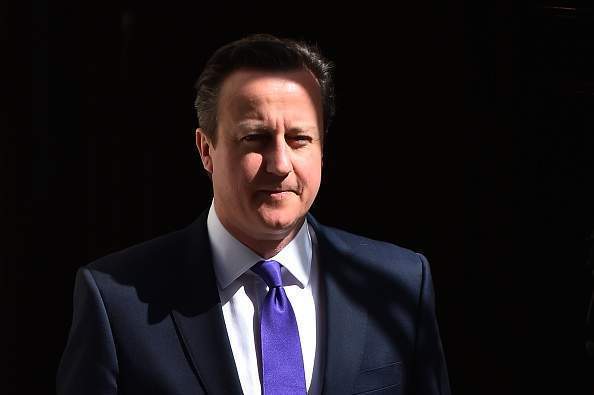

Twitter appears to have been more solid territory for Labour, with Ed Miliband himself having particular success. According to data from ElectUK, the app built by Tata Consultancy Services to monitor Twitter conversations during the election, the erstwhile Labour leader was responsible for three of the top six most retweeted political posts between 26 March and 7 May. Top of this list was his post about David Cameron refusing to attend the BBC election debate on 16 April, which garnered nearly 14,000 retweets. Meanwhile his criticism of Nigel Farage’s claim that immigrants with HIV are coming to the UK for free treatment received nearly 10,000.

Miliband was also the most talked about politician, with ElectUK data recording that he was the subject of 694,000 tweets, compared to David Cameron’s 616,000. However, the situation was a little different when it came to the most talked-about parties, with UKIP on top with 945,000 mentions. Labour was the subject of 881,000 tweets, while the SNP had the third highest amount with 587,000.

So what conclusions can we draw from this election, and what does it point to for the future? First, there is no doubt that social media is a vital platform for national discourse during elections. Sometimes it leads that discourse, either by breaking news as it happens or by giving politicians and parties the platform to get their voices heard. Other times, it provides a companion to traditional media, such as during the television debates when viewers gave their reactions on Twitter as and when events unfolded.

Second, the internet has changed the way we consume content. In the past we would be relatively passive consumers, receiving the information that our newspapers or the television channels gave us. Now we curate content ourselves; we can follow those on Twitter whose views we largely agree with and choose not to read online articles that we are less interested in. The result is that, although it was the polling companies that did most to mislead Labour supporters about the outcome of the election, the bubble of left-wing sentiment that Twitter users were able to self-create may have helped to obscure real-world opinion and the imminent defeat.

Finally, the UK may not have its own Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert, and the last series of The Thick of It may be edging into distant memory, but satire is alive and well on social media. Whether it was Ed Miliband being mixed into a song by the grime artist Skepta, a young Ed Miliband being compared to the Inbetweeners, or people simply replacing family photos with images of politicians, a sizeable proportion of the British public appeared determined to subvert the parties’ carefully stage-managed campaigns. And who can blame them.

Designed, built and delivered by Tata Consultancy Services, ElectUK turns your smartphone into an advanced social media analytics tool, giving voters the ability to identify and share online trends.

The app is free to download and is available on both iOS and Android devices. Just search for ‘ElectUK’ in the Apple Appstore or Google Play Store.

For more information, please visit www.tcs.com/ElectUK.

Please note: the ElectUK app analyses data and helps to identify trends in online conversations, it is not promoting or criticising any party or political view.