This article was originally published in May 2017. It has been republished in light of the continued interest in combatting fake news.

From writing a book on “post-truth politics”, I know that bullshit is effective, the internet is a great breeding ground for it, how it taps into modern politics, and why there’s a big business model behind it. But how can it be tackled? Here are some things you and I can do for ourselves.

Burst your bubble: If most of us exist in online filter bubbles, and those filter bubbles can shift our views away from the political mainstream, making an effort to break out of our own bubble can only be helpful. This needn’t be too drastic: following a handful of thoughtful people – not the people shouting most loudly – from the other side of an issue you care about on Facebook or Twitter is a good start. Trying to watch programmes or read articles from outlets on the other side of your own politics helps too. Knowing what people we disagree with actually say and think – rather than the straw men and caricatures we create in our heads – helps us bridge gaps, and makes it harder to demonise people whose politics are different from our own.

Engage System Two: System One is our instinctive reaction to a situation or new information, while System Two is our considered response. System One is effortless, and often quite satisfying to leave in the driving seat. When we’re browsing in this mode, it’s really easy just to click and share anything outrageous or heart-warming which reaffirms our worldview. That’s why this sort of material – which is often bullshit – performs so well on the internet. If we want to stop ourselves sharing this kind of material, just making ourselves stop and think, even for five or ten seconds – in other words, engaging System Two – makes us much less likely to share nonsense. Even just a few seconds’ thought lets us make several quick assessments. What’s the source of the information – is it from a major news outlet? A named politician? An anonymous account? Can we verify the claim that’s made? If we’re about to share a screenshot, does it seem credible – would the person concerned really say that? If we have doubts, we can easily and quickly Google for facts and find out what’s happening. Slowing down for even just a few seconds makes us much less likely to share bullshit.

Learn some stats: This one does not sound much fun, I’ll admit. But even a very basic grasp of statistics makes you much harder to fool. It’s not so much about memorising dozens of figures about the economy, but rather about being able to build up a series of mental shortcuts about whether or not numbers are plausible, or big. If we hear that the cost of benefit fraud is £1.3 billion a year,7 this number on its own doesn’t tell us much – it’s quite a lot of money, and more than any of us can really visualise. If we happen to know the rough amount the government spends on working-age benefits, or even just the total amount of government spending (around £780 billion), we can put the figure in context. Knowing the basics of how averages work, how percentages work and how to put figures in context gives us a lot of power to independently assess what we read – and doesn’t even require us to do too much maths. Tthe 1954 book How to Lie with Statistics by Darrell Huff is a great (and accessible) place to start.

[See also: Empower the people to win the war on disinformation]

Treat narratives you believe as sceptically as ones you don’t: By instinct, we tend to look for fact-checks and sceptical takes on narratives that conflict with our existing politics: if we’re liberal, we’re unlikely to have thought Hillary Clinton’s email scandal was a big deal, and would likely be sceptical of the Benghazi probes from Congress. If we’re a Donald Trump supporter, we’re not all that likely to think the allegations around Trump’s ties to Russia are particularly credible. We need to try to jump back from this and look for sceptical takes on the attack lines we believe – and also try to give credence to attack lines on causes and candidates we like. It may even help to try to mentally swap in a different politician or cause when reading a story and see if it would change our view. This is a big ask: it’s really tough to try to leave our politics behind when looking into a scandal, but if we can manage it, it’s great for our ability to actually assess facts and evidence – and to see why people we disagree with might be fired up by a scandal we’ve dismissed, and vice versa.

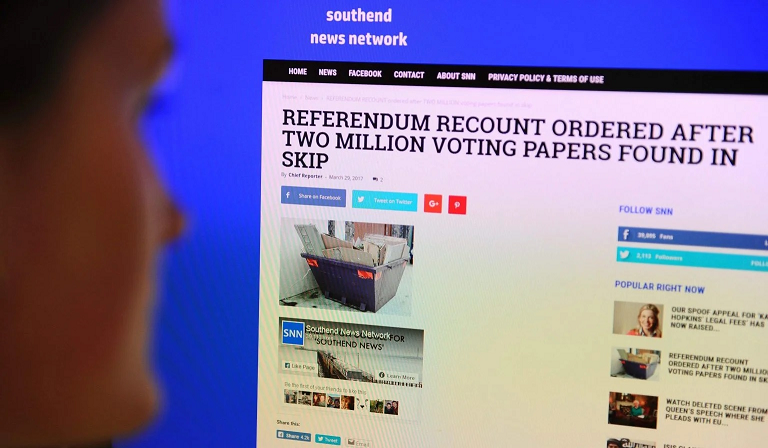

Try not to succumb to conspiratorial thinking: In the run-up to the Brexit vote, Leave supporters online urged one another to use pens in the voting booth, lest the authorities rub out their vote and change it to keep the UK in the EU. Left-wingers share stories of Theresa May directing contracts towards G4S because her husband owns shares in it (he doesn’t). Before the US election, Trump supporters warned of efforts to rig the vote, whether with millions of fake votes, with outright fraud or by denying Trump supporters their votes. After the election, elaborate and detailed (but evidence-free) anti-Trump theories – ‘time for some game theory’ – went viral time and again. Conspiracy theories are the enemy of reality-based coverage. These theories take isolated facts and use conjecture to join the dots, building elaborate narratives showing up their targets as malign and dangerous. Almost no real political scandal could ever live up to the imaginary ones conspiratorial thinking creates. The results are all damaging: they normalise bad behaviour – real malpractice is rarely as exciting as imagined scandal – while diminishing trust in political institutions and driving those who believe them to the political fringes. The post-truth era is accompanied by a rise in conspiratorial thinking on all sides. The more we can resist it, the better for all of us: we should fight to hold our politicians and our media accountable, but this should be based on hard evidence and thorough investigation. This might be less exciting than the conspiratorial version of history, but it’s surely more productive.

There will be no single solution to the rise of bullshit, and different players in the information ecosystem will all have to respond in different ways. We cannot build a solution which relies on good faith of everyone involved: we need to start from the politics and the media that we have, so proposals that rely on asking media outlets to reinvent their business model, or require millions of people who don’t pay for news to spontaneously start, are doomed. But we have to tackle it: a shared sense of reality, a counter to conspiracies, and some basic consensus are vital to a healthy democracy. A truly post-truth world is in none of our interests.

James Ball is the global editor of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and the author of Post Truth: How Bullshit Conquered the World (out now). This is an edited extract.

[See also: What does ‘elites’ mean, and why do they always rule?]