For the past few weeks, the Doctor has been circumnavigating the globe. Cardiff, London, Seoul, Sydney, New York, Mexico City, and wrapping up last night in Rio de Janeiro, Peter Capaldi is (literally) being introduced to the world in advance of his debut as the Twelfth Doctor. (Or wait, did we start over with the counting? How does John Hurt factor in again?) Capaldi’s first episode, “Deep Breath”, is getting a film-premiere-style event in Leicester Square on Saturday, which will be simulcast in hundreds of theatres around the world. The rest of us will watch it on plain old BBC One – or your local affiliate, in whatever country you live in. The world tour reflects the truly global reach of today’s Doctor Who, a show that now holds the record for “largest ever simulcast of a TV drama”, after 94 countries aired the 50th anniversary special at the same exact time last November.

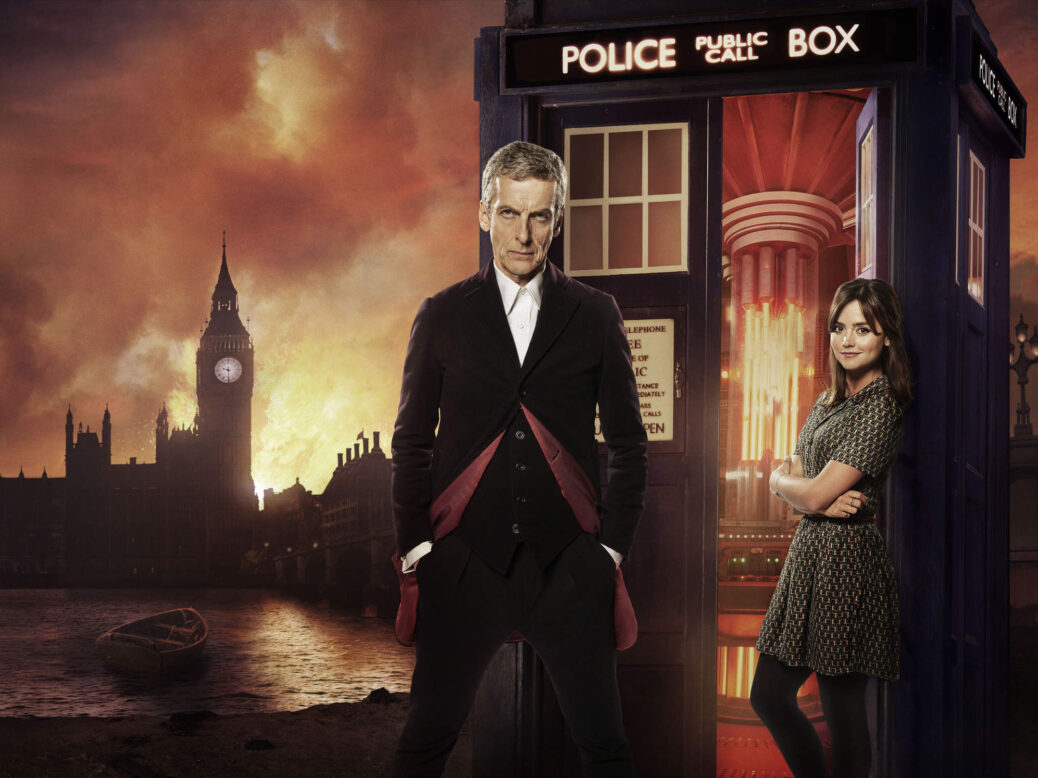

If you follow Doctor Who on social media – and I cannot recommend their joyful and incredibly fan-positive Tumblr highly enough – then you’ve seen slices of the world tour: Capaldi and Jenna Coleman in increasingly sharp outfits, strange-looking lost-in-translation moments onstage (Capaldi doing a very shy version of the twist in South Korea; Capaldi holding a sombrero in Mexico), and, most importantly, endless queues of fans. Sonic screwdrivers and fezzes, long brown coats and rainbow scarves, Weeping Angels and Cybermen and TARDIS dresses that never fail to inspire my deepest envy – we saw pictures of crowds around the world all looking pretty much the same, united by their love of a single thing: a British cultural institution, half a century old now, but with the potential for endless regeneration.