Alan Johnson on Paul McCartney

Joan Bakewell on George Harrison

Alan Johnson on Paul McCartney

I can’t quite remember if it was Susan Kelly or Christine Roberts who liked John best. I’m sure it was Pauline Bright who swore allegiance to George. If Ringo had an advocate in the “Who’s the best-looking Beatle?” debate taking part in our corner of west London I’ve forgotten who she was, but all the other girls I knew (and I knew a lot in 1964) were devoted to Paul.

Bliss was it in that dawn for music fans to be alive, but to be young was very heaven. This was the year that the Beatles’ status shifted from “British sensation” to “international phenomenon”; the year when Cathy McGowan announced to the nation live on Ready Steady Go! that “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was number one in the US Billboard Chart (at the same time as other Beatles releases stood at numbers two, three and four).

It was unimaginable that such a thing could happen. Since rock’n’roll began it had been stamped “Made in America”. With the exception of Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, everything worth listening to came from across the Atlantic. Our home-grown pop stars were Elvis Presley tribute acts that assumed a Memphis drawl to hide their Surbiton accents. Eventually they’d follow Tommy Steele into variety and sing the likes of “Little White Bull” for a family audience.

Now the hurricane of musicality from the Mersey had blown all that away.

The Beatles didn’t fit comfortably into the mods v rockers conflict of the time: we mods knew what music we didn’t like, which was basically anything associated with greasy-haired rockers. So, white artists such as Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Gene Vincent were reviled while Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley and Wilson Pickett were revered. The Beatles were certainly too successful for the ultra-mods, who prided themselves on liking artists who nobody had heard of.

We male devotees of the Fab Four adopted an air of condescending disdain when asked by our girlfriends to name a favourite. Our preference had to be bestowed with a more manly pretext than looks. For instance, we’d admire George’s guitar break on “All My Loving”, or John’s sense of humour.

But I liked Paul best predominantly because of his amazing looks. I so wanted to have those almond eyes, that perfect hair, the pouting lips. None of this could be admitted. Alone in the flat I shared with my sister, I’d use her old school hockey stick as a substitute bass guitar, holding it left-handed as I mimed in front of the mirror to the Beatles for Sale LP. When “Paperback Writer” was released I wondered at our secret affinity as much as any love-struck girl, because at the time I did want to be a paperback writer (as well as a rock star like Paul).

My love for the Beatles is such that I hate to promote my favourite by suggesting any imperfection in his colleagues but basically the only serious competition to Paul comes from John who, whisper it softly, was actually a bit of a rocker. I know, I know – I’ve seen those photos of Paul with his hair slicked back but that was in the Hamburg days. The thing is that John never seemed comfortable to leave that look behind him, whereas Paul fitted perfectly into the mop top and collarless jacket.

On stage, Lennon looked as if he was riding an imaginary motorbike, or perhaps a very thin horse: he stood, legs apart, doing little squats, with an unremarkable guitar hoisted too far up on his chest. (Those were the early days, before the Rickenbacker.) To his right he was gently upstaged by the cool and confident Paul, the Höfner bass a left-handed compliment to his individuality. And that McCartney voice, with its incredible range: one moment a gritty roar (“I’m Down”), the next a soft caress (“And I Love Her”).

I could never claim that Paul wrote better songs as some have tried to do. Leonard Bernstein once said “She’s Leaving Home” was equal to anything Schubert ever wrote. “And Your Bird Can Sing”, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “In My Life” would be enough to settle any argument that John’s output wasn’t at least as good as Paul’s.

It’s in the post-Beatles period that I believe Paul nudged ahead. For some inexplicable reason, this is the period where John was portrayed as cool and Paul as twee. It is true that “Imagine” received a better critical reception than “Mull of Kintyre” yet while both records sold millions, few Beatles fans would consider them the equal of the Lennon/McCartney canon. It’s also true that “The Frog Song” suggested Paul had morphed into Tommy Steele.

But I’ve been relistening to Wings (trying to forget that Alan Partridge called them the band the Beatles could have been). The Plastic Ono Band didn’t produce anything comparable to “Band on the Run”, or even “Venus and Mars”. Pre- and post-Wings, the music has flowed from Paul like a blackbird singing in the dead of night. I offer “Maybe I’m Amazed” – and Flowers in the Dirt, his amazing collaboration with the only artist worthy of a mention in the same breath as Lennon and McCartney, Elvis Costello.

Paul was my favourite Beatle and, having just reached the age of 64, I’m pushing Vera, Chuck and Dave off my knee to listen again to the single biggest influence on popular music that the world has ever known.

Alan Johnson’s memoir “This Boy” is published by Corgi (£7.99)

Terry Jones on John Lennon

I never really liked John. I thought he was too acerbic and critical. He always seemed to be the nasty one in the group – argumentative and awkward.

And then I caught myself listening to “Imagine”, time after time.

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too . . .

And I saw the light! The words speak for themselves: so pure and straightforward – so daring in their simplicity.

I was becoming fixated by the song. I started playing it on the piano, picking it out note by note. That week, on Monday 8 December, John Lennon was assassinated.

I’d first become aware of the Beatles when I was at Oxford – they were playing somewhere or other and I remember mocking the pun in the name. When I first heard them I was entranced, though still snooty about pop music. I bought Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band when it came out in 1967, the first Beatles LP to be recorded in stereo, I believe. I was won over.

When Lennon was killed, I really didn’t know how I felt about it. With “Imagine”, I had begun to see him in a different light – no longer as the argumentative one but as a sublime lyricist. I don’t know how I had overlooked that before. I was an easygoing type and didn’t like troublesome people. But when he died, in such a senseless way, I guess it drew me closer to John.

I looked at his other lyrics. I particularly liked his masterpiece “Grow Old With Me”, freely adapted from Robert Browning’s “Rabbi Ben Ezra”. I’d always thought the wonderful lines – “Two branches of one tree/Face the setting sun/When the day is done” – were from the original poem, but they aren’t. Lennon wasn’t frightened of saying “God bless our love” and for a thoroughgoing atheist he can be forgiven.

I began to love him for being a peace activist – moving to Manhattan in 1971, where his criticism of the Vietnam war resulted in a lengthy attempt by the Nixon administration to have him deported.

“Give Peace a Chance” was written during Lennon’s “bed-in” honeymoon at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, Montreal. A reporter asked him what he was trying to achieve by staying in bed and he returned: “Just give peace a chance.”

He recorded the song on 1 June 1969 at the same hotel. It was originally credited to Lennon-McCartney: he later said he regretted having been “guilty enough to give McCartney credit as co-writer on my first independent single instead of giving it to Yoko, who had actually written it with me”. I know the feeling.

I loved “Woman”, from the Double Fantasy album released in November 1980.

Woman, I can hardly express

My mixed emotion at my

thoughtlessness

And after all I’m for ever in your debt . . .

His marriage to Yoko Ono marked his transition from acerbic critic to warm and thoughtful man. Good for you, John. I love you now and for ever.

Joan Bakewell on George Harrison

I was working for Granada TV in Manchester in the Sixties when the word got round about this amazing new group – Beetles, but spelt wrong, people said. As I weighed them up, George seemed the odd one out. John had the wit, Paul had the glamour, but George . . . well, he seemed more thoughtful.

I like that, and have done ever since. I was over in Liverpool at the time, too, charting its amazing cultural flowering: Liverpool poets and playwrights as well as Liverpool bands. When I came to research my 2011 novel, She’s Leaving Home (yes, I stayed loyal!), I was in Liverpool again, meeting up with ageing DJs and archivists who’d kept records and memories of the Liverpool scene. I discovered that in the musical maelstrom that was the Sixties every kid on the block had a guitar, begged, borrowed or bought. It was as though a fever had seized the city.

And just like all his mates George was seized by it, too. In the ferment of music-making, dozens of groups were coming together, splitting, re-forming, trying out different players, searching for the right sound and the right people. That John and Paul found George was their great good fortune – and his.

It was Paul who found him, when he was only 14, and recruited him to come and hear the Quarrymen. They’d met on the bus to school: Paul was in the class above him. They were all from modest homes, state-educated at grammar schools. George’s dad was a bus conductor and George helped out with a butcher’s delivery round every Saturday morning. This was a time when lads borrowed each other’s records, got together in the bedrooms of council houses to rehearse and ventured to try out bookings at working men’s clubs. Paul and John had other guitarists for a while but somehow settled on George.

I can only guess that his sweet nature, his eagerness to work hard and his emergent musicality appealed to them. They knew he wouldn’t challenge the powerful talent of their double act but would meet their own standards of music and lifestyle. It was an ideal match. Even if the group didn’t have the serendipity of the best string quartets there was something about the balance of their talent and personalities that welded them in a unique way. George was to get angry, jealous, hurt at their estimate of his talents, and he hailed their break-up as a great escape. But, for those central Beatle years through the Sixties – through the tours, the singles, the albums and the films, George was exactly what was needed.

And the songs! How can a song with as mundane a title as “Something” lay claim to being one of the greatest love songs ever? At least that’s how Sinatra rated it, and, for what it’s worth, I agree. Its lyrics have the innocence and simplicity of the best poetry: “Something in the way she moves/Attracts me like no other lover . . .” How fine is that, harbouring an erotic charge that still gives me a thrill. And “Here Comes the Sun” – one of the gentlest, most beguiling tunes of the decade. On their early LPs it’s Lennon and McCartney who dominate. George hardly gets a look-in: but doesn’t seem to mind. He laughs and jokes through the film Help as much as they do. But towards the end of the Sixties his talent really emerged. He grew in confidence, started to think for himself and to take an interest in sitar music. Ideas were moving fast: the Beats and Zen had drifted over from America . . . Everything fed their appetites for the new.

Then they’re off to India and caught up in the Maharishi scam, but the whole exploit makes George more thoughtful. He worries about big things: the point of it all, what life is about, where we’re all going. Nothing too Nietzschean – but the big questions nonetheless. He wrote “All Things Must Pass” and “Living in the Material World”, and worried about doing good, being a good person. It was George who organised the great Concert for Bangladesh – the first great charity rock concert. It was there that “My Sweet Lord” proclaimed itself the anthem of swooned youth. It’s there, too, that “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” took to the big stage and became a classic.

George’s role in the Beatles was merely a prelude to a lifetime’s music-making. His partnership with Ravi Shankar, his creation – along with Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne – of the Traveling Wilburys, testify to a lifetime’s obsession with collaborating and being in groups.

But the Beatles were the first, and an extraordinary bond: for almost ten years the four shared an intimacy as close and as stressful as marriage; as the world lionised them, they grew together, sharing jokes, hairstyles, attitudes, perhaps women, certainly music. It shaped the outlook and expectations of the boy George, gave him a safe place to develop his identity and talent. And the strength to live his own life when the split came.

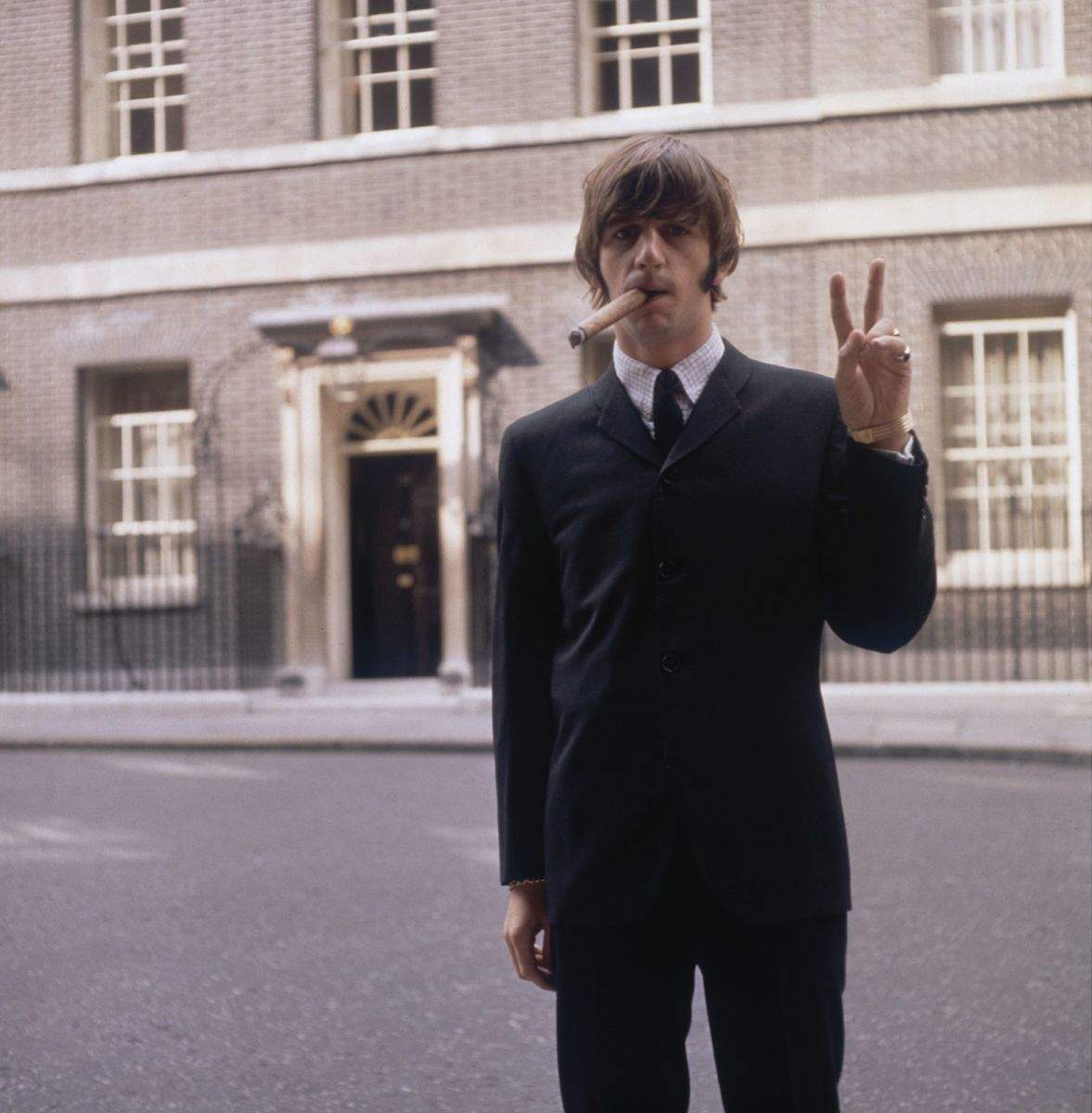

Geoff Lloyd on Ringo Starr

The prevailing wisdom on Ringo Starr owes much to a quotation from John Lennon. Asked if Starr was the best drummer in the world, Lennon quipped: “He’s not even the best drummer in the Beatles.” It’s a great joke, but Lennon never said it. Mark Lewisohn, the forensic Beatles historian, attributes it to a TV appearance by the comedian Jasper Carrott in 1983, three years after Lennon’s murder. In fact, Starr was held in high regard by his bandmates.

It is important to remember the circumstances in which he joined the Beatles in 1962. Lennon, Harrison and McCartney had long been unhappy with their drummer Pete Best, a rudimentary musician whose sullen personality spilled into stage performances. The band had signed to Parlophone and the label boss, George Martin, made it clear that Best’s drumming wouldn’t pass muster in the studio. The ambitious John, George and Paul took this as their cue to commit whatever the drummer-equivalent of regicide is (timpanicide?), and upgrade. These were cocksure young rock’n’rollers, at the top of the thriving Merseyside music scene, on the brink of a career as national recording artists. The decision to hire Ringo wasn’t made out of desperation to fill the position: it was a calculated gambit to headhunt the best drummer they knew.

Ringo’s musicianship is often subjected to a different standard of scrutiny from that of the other Beatles. He is accused of lacking technical ability, even though the same can be said of all the band members, none of whom had any formal music schooling. Lennon’s idiosyncratic guitar playing is lauded, but has its origins in transposing banjo chords that he learned from his mother, and McCartney’s reinvention of the bass guitar as a conduit for melody was born out of being lumbered with the instrument when Stuart Sutcliffe left the band. Ringo’s drumming style is just as unusual, and similarly rooted in accident: he was born left-handed but was forced to use his right by his superstitious grandmother. When he plays the drums, it’s a right-handed set-up but with the emphasis of a left-hander.

Unfavourable comparisons are drawn between Ringo and contemporaries such as Ginger Baker and Keith Moon, though Ringo’s difference is precisely what made him the perfect drummer for the Beatles. A rhythmic minimalist – he learned his craft before he could afford a car, and was able to carry only the bare bones of a drum kit on the bus – Starr has nothing of the showboat about him. He never overstates his case. The Beatles canon is rich with his intuition for marrying rhythm with song: the syncopated groove of “Anna (Go to Him)” on their debut album, the proto-big beats of “Rain” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”, the distant thunder rumblings on “A Day in the Life”, the oddball hi-hats that introduce “Come Together” . . . Of the 212 songs the Beatles released between 1962 and 1970, only one features a drum solo (“The End”, on their last recorded album, Abbey Road ). And Ringo agreed to this only under duress.

He was the first Beatle to leave the band, albeit briefly. Feeling isolated, he walked out in 1968 during sessions for The White Album. He came back a fortnight later, after some ego-massaging from his fellow band members, who filled the studio with flowers for his return.

In the Beatles’ latter years, Ringo formed his own publishing company, Startling Music, and made attempts at songwriting, most notably with “Octopus’s Garden”. Out of affection for him, the other members of the band lavished attention on the recording, bolstering an unremarkable tune with sound effects and vocal harmonies. When the Beatles began to disintegrate acrimoniously, Ringo was the least divisive figure, his late arrival into the group leaving him untainted by the residual schoolboy hierarchy of Lennon, McCartney and Harrison.

Post-Beatles, Ringo’s initial flush of solo hit singles and albums soon went into terminal decline due to his dearth of songwriting chops and vocal prowess. He took some film acting roles, buoyed by the success of his former band’s forays into cinema (some critics – erroneously – had described his screen presence as “Chaplinesque”). He also launched a short-lived furniture company, marketing doughnut-shaped fireplaces of his own design. He continues to tour, and to release albums with hideous titles (Vertical Man, Y Not, Ringo 2012). And a whole hour on Google Images suggests that his eyes haven’t been seen without the cover of sunglasses since the late 1980s.

Validation of Ringo’s primary talent, as a drummer, comes from his former bandmates, all of whom called on his services for solo albums. Not only was he the best drummer in the Beatles, he was the most popular Beatle within the Beatles.

Geoff Lloyd’s “Hometime Show” runs on weekdays on Absolute Radio (5pm)