Rowan Williams: We can connect with God quietly, in private, through words, posture and breath. Photograph: Linda Nylind/Guardian

The physicality of prayer

Rowan Williams

The Christianity I was originally formed in was not very ritual-minded: it was both intellectually alert and emotionally intense – the best of a style of Welsh Nonconformity now almost extinct – but tended to look down on physical expression of belief (other than singing, which I suspect was regarded as not really physical). Only when the family joined the Anglican Church when I was in my early teens, after we’d moved to another town, did I discover a sense of worship as a physical art, involving gesture, movement and colour. I still have a vivid memory of my first experience of a solemn Mass with procession at Easter, when I was, I suppose, about 12 – the awareness of a deliberate strategy of involving the senses at many levels.

The mild High Church atmosphere of those years was, for me, an environment that made strong imaginative and emotional sense, and indeed is still the kind of setting where I feel most instinctively at home, rather than in more simply word-oriented styles, or in the heated atmosphere of “charismatic” worship, repetitive song and unstructured prayer – although I’ve learned to be nourished by that, too, in many circumstances. But the ritual that is most significant for me apart from the routines of public worship and the daily recitation of the fixed words of morning and evening prayer owes more to non-Anglican sources.

Readers of Salinger’s Franny and Zooey will recall the somewhat unexpected appearance there of an account of the traditional Greek and Russian discipline of meditative repetition of the “Jesus Prayer” (“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner”). Practically every Eastern Orthodox writer on prayer will describe this, and many in the tradition also describe some of the physical disciplines that may be used to support it – being aware of your breathing, sitting in a certain way, focusing attention on your chest: “bringing the mind into the heart”, as the books characterise it.

The interest in uniting words with posture and breath is, of course, typical of non-Christian practices also; and over the years increasing exposure to and engagement with the Buddhist world in particular has made me aware of practices not unlike the “Jesus Prayer” and introduced me to disciplines that further enforce the stillness and physical focus that the prayer entails. Walking meditation, pacing very slowly and co-ordinating each step with an out-breath, is something I have found increasingly important as a preparation for a longer time of silence.

So: the regular ritual to begin the day when I’m in the house is a matter of an early rise and a brief walking meditation or sometimes a few slow prostrations, before squatting for 30 or 40 minutes (a low stool to support the thighs and reduce the weight on the lower legs) with the “Jesus Prayer”: repeating (usually silently) the words as I breathe out, leaving a moment between repetitions to notice the beating of the heart, which will slow down steadily over the period.

The prayer isn’t any kind of magical invocation or auto-suggestion – simply a vehicle to detach you slowly from distracted, wandering images and thoughts. These will happen, but you simply go on repeating the words and gently bringing attention back to them. If it is proceeding as it should, there is something like an indistinct picture or sensation of the inside of the body as a sort of hollow, a cave, in which breath comes and goes, with an underlying pulse. If you want to speak theologically about it, it’s a time when you are aware of your body as simply a place where life happens and where, therefore, God “happens”: a life lived in you.

So the day begins with a physically concrete and specific reminder that your own individual existence is breathed through by a life that isn’t your possession; and at moments of tension or anxiety during the day, deliberately breathing in and out a few times with the words of the prayer in mind connects you with this life that isn’t yours, immersing the anxiety and dispersing the tension – even if it doesn’t simply take away pain or doubt, solve problems or create some kind of spiritual bliss. The point is just to be connected again.

The mature practitioner (not me) will discover a steady clarity in the vision of self and world, and, in “advanced” states, an awareness of unbroken inner light, with the strong sense of an action going on within that is quite independent of your individual will – the prayer “praying itself”, not just human words but a connection between God transcendent and God present and within. Ritual anchors, ritual aligns, harmonises, relates. And what happens in the “Jesus Prayer” is just the way an individual can make real what is constantly going on in the larger-scale worship of the sacraments. The pity is that a lot of western Christianity these days finds all this increasingly alien. But I don’t think any one of us can begin to discover again what religion might mean unless we are prepared to expose ourselves to new ways of being in our bodies. But that’s a long story.

Rowan Williams was Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012

A walk with the imagination

Melvyn Bragg

Ritual practices that used to be confined to religious rites have now become secularised. From Homer, through Socrates, the Jews, Romans, Christians and all other known schemes of worship, ritual has been central to the observance of a creed.

Now we talk about the nesting rituals of birds, bargaining rituals in markets, the rituals of non-sexual actions in courtship, the rituals between waking up and getting to work, of games, of meeting and eating. Just about every social manoeuvre has been given a satisfying significance by what we would like to call ritual. We hold on to the word like a totem.

But the roots are still religious. And these roots are earthed in belief. In a way of being that began as an attempt to understand and explain the then otherwise inexplicable and continues, for some, in a conviction that there is more, or other, to life than can be described with certainty by reason alone.

Perhaps this can be ascribed to the hangover effect. We carry with us layers of previous generations, in manners, in language, in habits. It could be that the residual belief in belief is just another part of the debris of our inheritance, but one so deeply grounded that it lingers on long after the death of the initial inspiration.

Of course, to millions of earthlings today, belief in the ancient sense is still a given. It is as inevitable a part of the day as sunset. And this is not only a phenomenon of “emerging” countries. The United States has a fair claim to be the most religious country on the planet.

Still, for those, like myself, whose early faith has ebbed so far away that it is over the horizon, the fundamental notions of religion have gone. The Resurrection? Surely not in a material world. Eternal life? A brilliant bribe. Miracles? Fables. God? The Big Bang. For us the sacred still reverenced for its hope, peace and beauty by so many has been skittled by the Enlightenment.

Yet in my case and perhaps in others, something remains. Perhaps it is prompted by a spiritual space so assiduously dug out in my childhood that it seems still to be in need of nourishment from a like sensation. The mysteries, visited on a young mind with force, which now appear like falsities, seem to have struck a chord too deep to be forgotten.

It is reassuringly commonplace to hear people talk about the peace or beauty they find in nature. I am writing this in Cumbria, a home of pantheism, the open library of a nature poet of genius. But Wordsworth’s nature always reverted to human nature and “the bliss of solitude” was inward. What he’d fed on was out there. And out there was felt, an impulse, rather than a deduction.

For many of us who walk in places of drama or beauty it is as if we are enveloped in an atmosphere that it’s a pleasure not to understand. As if we want not to know but to feel. And not to know why we feel.

The rituals of walking are few but often seem essential. The garb, the route, the recognition of old favourites – trees, prospects, rivers. Once you are in the rhythm of those rituals what happens, to me at any rate, is that a non-self takes over. A non-drug-induced drift. And an expanding sense of inner freedom. And there are the inklings of sensations. Intimations? Shapes that could become thoughts that do not seem to obey mechanical laws. Maybe in time we will see that in fact they do. Maybe everything we feel will be settled by mathematics. But what if not? Might the known unknown of the universe and the brain surprise us all? And will we then lose this invaluable feeling of inner liberty?

Such a reflection can be dismissed easily as sentimental or as a sort of non-thinking, or unreasoning, sin of sins. Yet sensations precede reason. Reason is a second tier. We are the multiple beings we are through our cascades of sensation. Imagination, scarcely understood, is let out to play during these solitary walks and is perhaps pointing us to communications which, in a few

hundred years, will seem as natural as quantum physics.

It could be that in solitude, with the luck of nature combining with a willing mind and time to let it roll through this strange, boundless creation inside the skull, we are looking to find . . . ? And the circle closes. Surely it can’t be a new Belief system.

Melvyn Bragg is a writer and broadcaster

Life in a different kind of time

Lucy Winkett

I recently bought a new toothbrush. It’s my first electric one and it’s very clever: it tells me when the prescribed two minutes are up. I can even set it to sound an alarm for each 30-second segment for each quadrant of my mouth. And the perhaps unsurprising truth is that I am simply incapable of brushing my teeth in any order other than the order in which I always brush them. It’s common to call this kind of repetitious and regular behaviour ritualistic, but I’m not sure where the line lies between ritual, habit and routine.

Much of my professional life as an Anglican priest has been concerned not only with private but with public ritual, both inside and outside the church building. This takes the form of ordered, collective, symbolic action that somehow expresses deep and often unsayable emotions. Pride, grief, respect, awe, love can all be found underpinning the ritualistic gatherings of weddings, funerals and baptisms. One of my abiding memories of my time as a canon at St Paul’s Cathedral was from the week after the 7 July bombings in 2005, when at midday bells were rung, taxis and buses pulled over and people poured out of nearby offices, shops and cafés in order to perform together a public ritual; to stand together in silence, remembering those who had died and reclaiming the streets from those who would make us afraid.

Public ritual, in its repetition, its use of symbols, sound, silence, its regularity and ordinariness, provides a kind of framework within which not everything has to be explained. Take baptising a child; it’s one of the most lovely duties of a priest. The three symbols of oil, water and light are given expression in anointing the child with the sign of the cross, baptising the child with water and then giving the parents a lighted candle. There is broad agreement that something rather fabulous is being celebrated. But if I stopped a service at the point where water is poured over the child’s head and asked everyone present precisely what was happening, I would hear as many answers as there were people. Is that a problem? It would have been a problem for my predecessors if the ritual were being used, as in the past, as an agent of social control. But now, in a century when I can assume that the gathered congregation is free to express dissent for itself, it doesn’t worry me at all, because the best ritual is deeply ambiguous and, in its ambiguity, is a form of peaceful and beautiful resistance against all that would reduce or attempt to atomise the mysterious realities of life and death.

In theological terms, rituals are performed at the crossroads where time meets eternity; where chronos meets kairos. We live our lives earthbound and rushing: metaphorically looking at the second hand on a clock. It’s accurate, but not a good way of telling the time. Rituals are performed, as it were, by the hour hand; imperceptible movement, no less true but a lot less anxious. Rituals help us do nothing less than live a different kind of time.

In the case of public ritual, the relationship between ritual and belief is a complex one, too. In an age where we are very fearful of being thought hypocritical, it is perhaps not a bad thing that the number of people being baptised is lower than it used to be; but surely a deeper question is: do I have to believe before I take part in the ritual, or does the ritual help to shape my belief? Just getting on and doing things before we know exactly what we’re doing, or why, can be a learning experience in itself. My own tendency is to blur the boundaries between ritual and belief, not because I think they are not important, but because I think they are easily distorted by people who claim the power to define what they are.

If rituals help us navigate the thresholds of life when emotion is high and the tectonic plates of desire, fear, hope and despair collide, then the truth is that I travel a long way not just when I’m celebrating the Eucharist but while I’m walking the dog. Ordinary life is full of grief and miracles. Rituals are performed at the boundaries, on the border. What we do almost every day, sometimes without noticing, is step over the line.

Lucy Winkett is the rector of St James’s Church, Piccadilly

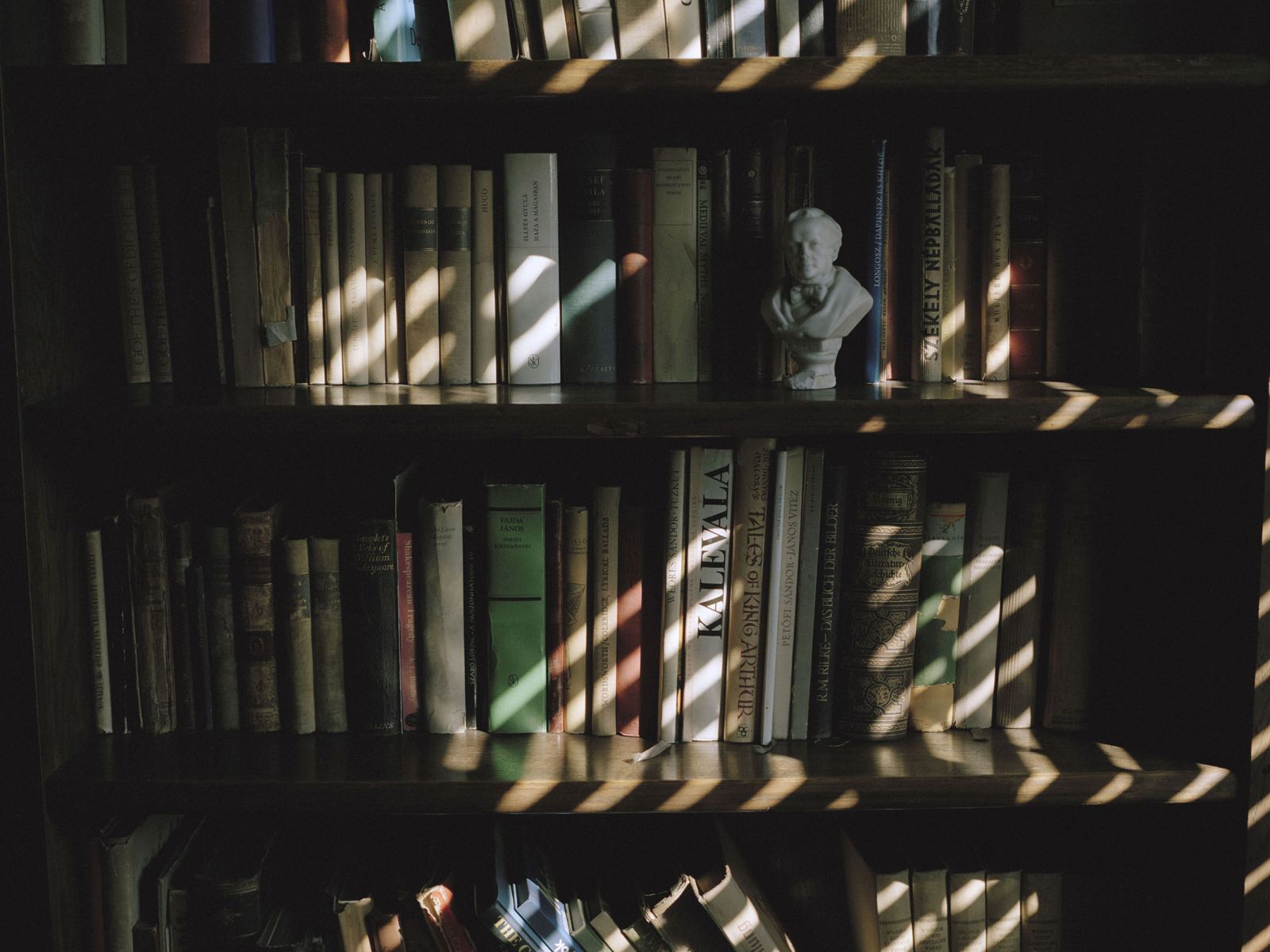

Shelf life: books furnish mind, room and spirit.

Photograph: Matthew Somorjay/Millennium Images

Choices, choices: could I be a bookshop?

Robin Ince

Hints of paranoia dog me, the sense of being scrutinised – but that all evaporates in the bookshop.

Most of my working life is trains. I go from town to town, like the Fugitive or David Banner, but without the sense of pursuit by law-enforcers.

My earnings are not for the show I will do in the evening – that is pleasure. They cover the cost of being away from my family and sitting on a packed train, positioned somewhere between an overflowing bin and a malfunctioning toilet. I occupy my time experiencing train theatre, the small playlets of anger, desire and melancholy that take place in the seats and vestibule area. The furious phone calls with alibis from drunken business people explaining they were kept late at work; the sad-faced man who failed to press the lock button on the toilet, now shrivelled after shrieking, “Close the door!” with his trousers round his ankles and his newspaper on his lap. The door will not close until it has opened fully first – and so all the travellers have experienced a Beckett short adapted by Ray Cooney.

But most of my time is spent in other worlds, in the pages of the second-hand books that increasingly bulk up my rucksack as I investigate the bookshops of each town I visit.

The carriage is not a means of transport. It becomes a hectic library, where I can drink tea, flick the crumbs of my cake from the hinge of a book, and read on, occasionally looking up to view alpacas on disused factories, or hillsides. While at night I must be gregarious with a few hundred people, by day I can be solitary.

My greatest joy is browsing books in seaside towns. There I am lost. The delight of the second-hand bookshop is the delight of surprise. New bookshops are pleasurable but we know what lies within. Yet in the second-hand, who knows what nonagenarian ufologist or furtive philosopher has died and their boxed books have found their way on to the counter.

I am rarely looking for anything in particular. I am looking for everything in particular. Many of my childhood weekends were spent with my father, browsing through bookshops with warped shelves and idiosyncratic cataloguing techniques. Nature and nurture have combined to make me an obsessive.

Desmond Morris once described the finding of a rare book as being the modern equivalent of stalking and killing mighty prey. The tribe rejoices. I am not sure my wife has the same sense of glee when I bring back another satchel of Pelicans and Penguins. Sometimes I find myself taking the back footpath and popping them under the shed until she has gone out. I fear that one day

my house will sink into the ground, leaving visible only a chimney pot. Just as John Peel had to reinforce the foundations of his garage to support the weight of vinyl, I may have to call the architects in.

I see myself as an overly self-conscious human being. Hints of paranoia dog me, the sense of being scrutinised, yet that all evaporates in the bookshop. I am mesmerised by the spines – almost unconscious, until I see something with an alluring title or enigmatic cover.

Then it’s the leafing through. Do I need this book? What weight is my rucksack already? Is this purchase worth the extra tingling of sciatica it may bring on? My mind must map the shop. The most labyrinthine are a delightful challenge. When I get to the end of the browsing, I must recall where each possibility is and return for a decision.

Once the books are bought, I retreat to a tea shop, preferably one with an elaborate Victoria sponge in the window, and pore over the new purchases. Inside each book is the hope of a new way of seeing the world; each one is a potential adventure. There can be the additional joy of finding some ephemera left by the previous reader: a pressed flower, a bookmark, an old postcard of Budleigh Salterton sent by “Isobel”, with the story of a beach hut and errant gull.

I like losing myself in those shops that were once houses, where each room is book upon book – and perhaps sheet music and some National Geographics. As a child, I went to the Cottage Bookshop in Penn, its rows so narrow it was barely possible to tilt your head back far enough to read the upper shelves. The attic room had a lock on it; not due to the madness of the owner’s first wife – this was where the collectibles were kept, and sometimes I snuck in with my dad. And no trip to Eastbourne is complete without a visit to Camilla’s. Should all the bricks disappear, the structural integrity would remain from books alone. There is a tea shop two doors down; its cakes are mighty.

Some people wish to be buried at sea, others scattered on a hillside. I wonder if the matter that makes me could be transmogrified into a bookshelf?

Robin Ince is on tour and will be appearing at the Latitude Festival on 19 and 20 July

Switch from online to off

Vicky Beeching

A few weeks ago at Westminster Tube station I watched as, seemingly in slow motion, my iPhone slipped out of my fingers, dangled momentarily at the end of its white headphone cable, then disappeared into the gap between the train carriage and the platform. Horror flooded through me. I stood transfixed, like in a Lord of the Rings re-enactment, watching as my “Precious” slowly fell into the abyss below. I literally found myself squeaking out a pained “Noooooo!”. Which made everyone turn round and notice. Which was then doubly embarrassing.

Hunting for a member of Underground staff, I felt sure they could reunite me with my iPhone easily and quickly. When they broke the news that nothing could be rescued from the tracks before the trains stopped running at 2am, I welled up. Which was of course rather embarrassing again. “It’s just a phone, love!” the cheerful chap said. “Come back tomorrow at 6am and we’ll have it for you.” “Yup, just a phone . . .” I mumbled absent-mindedly as I walked away, counting on my fingers just how many long hours lay between then and 6am.

Travelling onward from that station I felt increasingly like a small child lost in a giant universe. I wanted to call a friend – couldn’t. Wanted to fire off an email, listen to a tune on Spotify, or check in with my Twitter community – couldn’t. Wanted to map my route from the next station to my business meeting – couldn’t. Arriving very late, as I’d had no “blue dot” to point me in the right direction, I felt almost panicky. The reliance I’d developed on a small piece of rectangular plastic and glass was stunning.

The science fiction writer and journalist Cory Doctorow once referred to technological gadgetry as our “outboard brain”. I totally resonate with that, having felt mine suddenly removed in an unexpected digital lobotomy. It felt like the chopping off of a limb, albeit a virtual one. Every few seconds I found myself thinking of something I needed to do, reaching into my pocket, then remembering I didn’t have the “outboard brain” required to complete the task. I was badly addicted and knew I needed to go cold turkey, so I tried to embrace the silver lining that day contained.

Smartphone-free, I noticed throughout the afternoon and evening that I’d regained the natural pauses that happen between events. No screen to gaze into while commuting, no email to check in the coffee queue, no Instagram photo to snap of my dinner before eating it. Life had breathing spaces again. Moments to process thoughts, rather than just consume yet more information. Yes, I felt oddly disconnected from my virtual community; oddly alone, but in a way that reminded me how much I needed to do so on purpose.

.jpg) If I had to name two things in life that keep me sane they would be silence and solitude. I’m a big introvert (think semi-hermit) and grew up in the countryside, where I’d spend hours walking through the fields on my own, or climbing to the top of trees and hiding there all day in a lofty lookout position. Yet I’m also a tech-geek and love social media. The two have existed in tension for me over the years. Losing my iPhone was a wake-up call that silence and solitude need to be carved out in my daily and weekly routine, like sacred rituals, or else they just won’t happen.

If I had to name two things in life that keep me sane they would be silence and solitude. I’m a big introvert (think semi-hermit) and grew up in the countryside, where I’d spend hours walking through the fields on my own, or climbing to the top of trees and hiding there all day in a lofty lookout position. Yet I’m also a tech-geek and love social media. The two have existed in tension for me over the years. Losing my iPhone was a wake-up call that silence and solitude need to be carved out in my daily and weekly routine, like sacred rituals, or else they just won’t happen.

I do spend a lot of time alone, yet with my “outboard brain” ever present, it’s not truly solitude. When I’m alone I’m not in physical conversation with anyone (unless I’m talking to myself, which naturally I’d never admit to . . .), but I’m not truly silent, as I am constantly tweeting, texting and emailing. Mobile tech has made silence and solitude both unfashionable and unnecessary; they’ve become the two ugly sisters of modern society. Online connectivity numbs the need to feel either, so why would we? Yet they have a power that many through the ages, of all faiths and none, have realised we desperately need.

In the light of my phone-dropping experience, I decided I needed to restart a ritual that I have loved since my teens but gradually given less time to: the silent retreat – going away to a spiritually inspiring location, which for me usually constitutes a monastery or convent, switching everything off except my wristwatch, and being totally silent for at least 24 hours. Initially it always feels like sudden immersion in water: a shock, painful. The struggle kicks up within me. Then it feels like a gradual stripping; facing my inner world, seeing it increasingly laid bare without the layers of busyness to conceal it. Finally, I settle in and my soul inhales the fresh air of quiet space, feeling life rush into every exhausted corner of my mind and heart.

I would love to practise this ritual every week, but realistically I’ll aim for monthly. If you’ve never braved a day or two of this, it’s formative indeed. Scary at first, but life-changing in its potential to bring clarity, courage and creativity. As a society, we usually avoid silence and solitude. Yet I believe they might be the medicine that we need most.

They stand as faithful guardians to keep us in tune with our inner selves in the constant, connective chaos of an exciting but relentless digital age.

Vicky Beeching is a theologian, writer and broadcaster researching the ethics of online technology

Stop, think, chew

Julian Baggini

I don’t miss the major rituals of Christian life. Weddings, births, deaths and remembrances are no less moving for the loss of a man in a dress and a little incense. Indeed, some secular equivalents can be even more powerful. The United States demonstrated this with its first-anniversary commemoration of 9/11, in which a Ground Zero ceremony consisting almost entirely of the recitation of the names of those lost had a profound, understated emotional resonance that no church service could match.

Where I think we atheists can be at a disadvantage is in the loss of the small, everyday rituals of prayer. When this is understood as intercession, I take it to be a kind of pure nonsense we are better off without. But prayer at its best is much more than this. Prayer offers an opportunity to reflect on our quotidian weaknesses, frequent failings, large and small. This should not be a prompt to self-flagellation, but an encouragement to do better tomorrow, humbly accepting that “better” will never be more than barely good enough.

Prayer also provides an opportunity to cultivate appropriate gratitude. We are not always lucky, and there is a kind of religious mania that leads people to thank God for whatever happens in their lives, no matter how horrendous. Nevertheless, most of us would do better to think more of what we do have than to dwell on what we don’t. Even if the grass really is greener on the other side, looking longingly at it too much just makes our own perfectly adequate fields look browner than they are.

I do not, however, think that the way to achieve this is to replace religious rituals with secular ones. There is nothing to stop us saying a secular grace, for instance, but to most of us it would sound artificial and contrived. It’s not that you need someone to thank in order to feel thankful – just that without the obligations of faith and the weight of history, self-created rituals of grace ring hollow.

A more promising alternative is to replace prayer with a regular period of quiet reflection. But without the religious imperative to maintaining the habit, this, too, is something that few of us, I think, are likely to sustain.

Rather than looking for secular surrogates, we should look for other ways to cultivate the virtues that ritual promotes. Such practices need to be at least as embedded in our daily routines as prayers are for believers.

The key is simply to attend as much to how we do things as to what we do. Take eating. We do not need to say grace to get into the habit of being grateful for what we have. Indeed, if we cultivate a proper sense of appreciation, we could do better than those autopilot believers who parrot their grace before mindlessly chowing down. There is nothing special we need do to achieve this, no incantation we need repeat before lifting fork to mouth. All we need do is to practise a kind of mindfulness when we eat.

It shouldn’t stop with ingestion. Our attitudes to waste can also help foster gratitude. It may have become a cliché that those who lived through the war never threw away a scrap, but our disposable generation would do well to recapture the sense of thankfulness that sat behind their zealous hatred of waste. Principled opposition to waste can become a convenient excuse for gluttony, so sometimes it is better to leave food uneaten than it is to overstuff an already full belly. But the casualness with which too many of us discard excess food reflects and reinforces a distasteful lack of gratitude that we would do well to counter.

Rituals are of use only to the extent that they encourage good habits of thought and behaviour. Their strength is in the way in which they weave themselves into the warp and weft of daily life. Their weakness is that they can become automatic and in some sense exist slightly to one side, in special, set-aside moments and places. A more direct method of appropriating their benefits is to attend directly to our own habits and build the right ones.

What this does not give us is any sense of the numinous. This is another loss, one that we should accept as inevitable, but that is not without compensation. Secular habits of gratitude and self-appraisal can give us a more acute sense of the value of the here and now. The immanent world can be the source of as much deep feeling as the transcendent. The poignant sense that all will pass and nothing will last is what roots true gratitude and a desire to make the most of our lives rather than squander our time on things that don’t matter, such as petty grievances and feuds.

So, although religious rituals belong to a form of life that may cultivate certain important ethical emotions, they also distract us with what seem like glimpses of another world. Unbelievers should replace rituals with good habits, and so take regular reflection more deeply into the fabric of everyday, mortal life.

Julian Baggini’s books include “The Virtues of the Table” (Granta Books, £14.99). He will appear at the Salon London Breakfast at the Latitude Festival later this month