Look, I don’t mean to be funny, but is there something in the water supply? When Mark Lilla wrote his jeremiad against “identity liberalism” in the New York Times, it was comprehensively picked over and rebutted. But this zombie take has risen again. In the last 24 hours, all these tweets have drifted across my timeline:

And then this (now deleted, I think, probably because I was mean about it on Twitter).

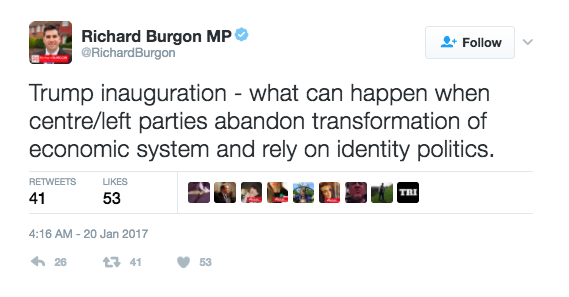

And finally, for the hat-trick . . .

Isn’t it beautiful to see a Blairite, a Liberal Leaver and a Corbynite come together like this? Maybe there is a future for cross-spectrum, consensual politics in this country.

These are all versions of a criticism which has swilled around since Bernie Sanders entered the US presidential race, and ran on a platform of economic populism. They have been turbocharged by Sanders’ criticisms since the result, where he blamed Clinton’s loss on her attempt to carve up the electorate into narrow groups. And they are now repeated ad nauseam by anyone wanting to sound profound: what if, like, Black Lives Matter are the real racists, yeah? Because they talk about race all the time.

This glib analysis has the logical endpoint that if only people didn’t point out racism or sexism or homophobia, those things would be less of a problem. Talking about them is counterproductive, because it puts people’s backs up (for a given definition of “people”). She who smelt it, dealt it.

Now, I have strong criticisms of what I would call Pure Identity Politics, unmoored from economics or structural concerns. I have trouble with the idea of Caitlyn Jenner as an “LGBT icon”, given her longstanding opposition to gay marriage and her support for an administration whose vice-president appears to think you can electrocute the gay out of people. I celebrate female leaders even if I don’t agree with their politics, because there shouldn’t be an additional Goodness Test which women have to pass to be deemed worthy of the same opportunities as men. But I don’t think feminism’s job is done when there are simply a few more female CEOs or political leaders, particularly if (as is now the case) those women are more likely than their male peers to be childless. Role models only get you so far. Structures are important too.

I also think there are fair criticisms to be made of the Clinton campaign, which was brave – or foolish, depending on your taste – to associate her so explicitly with progressive causes. Stephen Bush and I have talked on the podcast about how hard Barack Obama worked to reassure White America that he wasn’t threatening, earning himself the ire of the likes of Cornel West. Hillary Clinton was less mindful of the feelings of both White America and Male America, running an advert explicitly addressed to African-Americans, and using (as James Morris pointed out to me on Twitter) the slogan “I’m With Her”.

Watching back old Barack Obama clips (look, everyone needs a hobby), it’s notable how many times he stressed the “united” in “united states of America”. It felt as though he was trying to usher in a post-racial age by the sheer force of his rhetoric.

As Obama told Ta-Nehisi Coates during his last days in office, he thought deeply about how to appeal to all races:

“How do I pull all these different strains together: Kenya and Hawaii and Kansas, and white and black and Asian—how does that fit? And through action, through work, I suddenly see myself as part of the bigger process for, yes, delivering justice for the [African American community] and specifically the South Side community, the low-income people—justice on behalf of the African American community. But also thereby promoting my ideas of justice and equality and empathy that my mother taught me were universal. So I’m in a position to understand those essential parts of me not as separate and apart from any particular community but connected to every community.”

Clinton’s mistake was perhaps that she thought this caution was no longer needed.

So there are criticisms of “identity politics” that I accept, even as I wearily feel that – like “neoliberalism” – it has become a bogeyman, a dumpster for anything that people don’t like but don’t care to articulate more fully.

But there are caveats, and very good reasons why anyone pretending to a sophisticated analysis of politics shouldn’t say that “identity politics caused Trump”.

The first is that if you have an identity that any way marks you out from the norm, you can’t change that. Hillary Clinton couldn’t not be the first woman candidate from a major party running for the US presidency. She either had to embrace it, or downplay it. Donald Trump faced no such decision.

The second is that, actually, Clinton didn’t run an explicitly identity-focused campaign on the ground, at least not in terms of her being a woman. Through the prism of the press, and because of the rubbernecker’s dream that is misogyny on social media, her gender inevitably loomed large. But as Rebecca Solnit wrote in the LRB:

“The Vox journalist David Roberts did a word-frequency analysis on Clinton’s campaign speeches and concluded that she mostly talked about workers, jobs, education and the economy, exactly the things she was berated for neglecting. She mentioned jobs almost 600 times, racism, women’s rights and abortion a few dozen times each. But she was assumed to be talking about her gender all the time, though it was everyone else who couldn’t shut up about it.”

My final problem with the “identity politics caused Trump” argument is that it assumes that explicit appeals to whiteness and masculinity are not identity politics. That calling Mexicans “rapists” and promising to build a wall to keep them out is not identity politics. That promising to “make America great again” at the expense of the Chinese or other trading partners is not identity politics. That selling a candidate as an unreconstructed alpha male is not identity politics. When you put it that way, I do accept that identity politics caused Trump. But I’m guessing that’s not what people mean when they criticise identity politics.

Let’s be clear: America is a country built on identity politics. The “all men” who were created equal notably excluded a huge number of Americans. Jim Crow laws were nothing if not identity politics. The electoral college was instituted to benefit southern slave-owners. This year’s voting restrictions disproportionately affected populations which lean Democrat. There is no way to fight this without prompting a backlash: that’s what happens when you demand that the privileged give up some of their perks.

I don’t know what the “identity politics caused Trump” guys want gay rights campaigners, anti-racism activists or feminists to do. Those on the left, like Richard Burgon, seem to want a “no war but the class war” approach, which would be all very well if race and gender didn’t intersect with economics (the majority of unpaid care falls squarely on women; in the US, black households have far fewer assets than white ones.)

Those on the right, like Daniel Hannan, seem to just want people banging on about racism and homophobia to shut up because he, personally, finds it boring. Perhaps they don’t know any old English poetry with which to delight their followers instead. (Actually, I think Hannan might have hit on an important psychological factor in some of these critiques: when conversations centre on anti-racism, feminism and other identity movements, white men don’t benefit from their usual unearned assumption of expertise in the subject at hand. No wonder they find discussion of them boring.)

Both of these criticisms end up in the same place. Pipe down, ladies. By complaining, you’re only making it worse. Hush now, Black Lives Matter: white people find your message alienating. We’ll sort out police racism… well, eventually. Probably. Just hold tight and see how it goes. Look, gay people, could you be a trifle… less gay? It’s distracting.

I’m here all day for a discussion about the best tactics for progressive campaigners to use. I’m sympathetic to the argument that furious tweets, and even marches, have limited effect compared with other types of resistance.

But I can’t stand by while a candidate wins on an identity-based platform, in a political system shaped by identity, and it’s apparently the fault of the other side for talking too much about identity.