When Greg Dyke was appointed Director-General of the BBC and was received by the staff of the great Kafkaesque edifice, he was reported as saying that it was “hideously white”. The liberal elite, especially those who have had a job in Britain’s late twentieth century race relations industry, wear their badges of courage and conviction right out there – as proud as the designer labels and vulgar slogans on the T-shirts of the hoi polloi. He obviously saw a lot of female faces and bodies as he surveyed the “human resources” of the organisation and it would been anathema to announce at the same time that he could discern the sexual orientation of employees and so assess whether the organisation was also “painfully straight”.

Mr Dyke (or is he Sir Greg now?) was making a political head-counting statement, one that reflects the concern that in a society whose population is four per cent black and brown there ought to be four black and brown people out of every hundred employed by a Corporation which is, perhaps after parliament, the showcase of the nation.

A phrase which adds a severe description to “white”, using the word in a racial sense, is a contention and that contention has a history. Neglecting the fact that there were runaway slaves and adventurers of several sorts from all over the globe in Elizabethan times and that Nehru, Gandhi and others sojourned in Britain as scholars in the era when Western education was deemed the most valuable and progressive in India, mass immigration established itself in Britain several decades after broadcasting.

There are at the time of writing this several BBC programmes featuring black and Asian people. They will, as tastes and fashions progress, be short-lived and be replaced in time by others. A critical commentary saying that a current situation comedy called Citizen Khan has taken multicultural broadcasting back several decades will carry no conviction, cut no ice, unless the history of British broadcasting featuring ethnic communities is evoked.

Immigration from the ex-colonies

The movement of labour from the ex-colonies to Britain began in earnest in the late

Fifties and early Sixties. There were no social or political plans, no vision for their integration into British society. They were left to find or form their own ghettos, to work the night shifts and the Underground, clean the streets, nurse the sick in hospitals, conduct the buses of the big cities and, in time, set up the mosque-and-mill enclaves of the midlands and the north and, aided by municipal socialism, the crime-prone vertical slums of London.

The first liberal impulse of the broadcasters was directed towards the Asian peasantry, the Indians and Pakistanis who came in the largest numbers from the Punjab, from Mirpur in what is now Pakistani Kashmir and from Bangladesh, then East Pakistan. The BBC’s first instinct was “integration” – teaching the newcomers to accommodate to British ways and British society – how to get about using the language, how not to bargain at supermarket counters but pay the price that the till rang up and elementary rules of etiquette. They ran programmes with well-intentioned, patronising titles such as Apnaa Hi Ghar Samajhye which means Consider It Your Home – “it” meaning Britain. There were other programmes in which white and Asian neighbours befriended each other and cultures rubbed along with pointed explanation, again with the aim of instructing the immigrant to feel at home. A famous programme was Padosi, Hindustani for Neighbours – years before the Ozzies named their soap.

Television didn’t consider that West Indians needed instructional programming to assist the assimilation. Black (or was it “coloured”?) characters went straight into situation comedies in bit or secondary parts. One or two Asian characters crept into Newcomers, a soap whose “native” writers, unfamiliar with the idiom of the newcomers relied on the uncertain advice of the rare black or Asian Rada-trained actor.

The empire strikes (limps?) back

Settlement gave rise to dissatisfactions, tensions, political formations and demands. There was the paramount question of how temporary was this influx of ex-colonials. Were they here to stay? Was the dream of some of them to live frugally, work hard and earn enough money to return home as relatively rich citizens, capable of buying property and setting themselves up in business in the Punjab or Jamaica defeated by the hand to mouth of immigrant employment and pay? It soon became clear that the road back was paved with yellow bricks – it was a fantasy.

One of the mainly Bangladeshi anti-racist demonstrations in the East End of London, protesting a spate of Paki-bashing and fire-bomb assaults on the estate flats of immigrants was “Come what may we are here to stay”, though the tones in which it was shouted was loaded with nostalgia and foreboding. Campaigning groups, some in imitation of the rise of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panther Party of the USA, began to demand equality in housing, schooling, and employment, in treatment from the police and the courts and in access to public facilities. There was manifest if not universal discrimination towards the new “coloured” populations in all these fields and the agitation took notice of and opposed them.

There was polite begging for relief but there was also bumptious militancy. The post-colonial era was also the post-war era and while Britain’s population looked forward to an acceleration in meritocracy, it also underwent the trauma of revisionist history in which the white man, conqueror, colonialist, imperialist, racist, slave-dealer and owner, composer of nasty nursery rhymes etc was often portrayed as the natural villain. Britain had just been through the era of the Angry Young Men, the post-war generation of playwrights, novelists and rebels who as the first tide of literary meritocrats saw class as their target. Now here was a new wave of objectors and claimants.

The agitation took to the streets in several instances – in protest, for example, against Enoch Powell’s 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech. In the USA, one could see a link between the civil rights agitation and the new wave of feminist protest. In Britain, the link may not have existed or been clear but together with the movements on immigration and race, feminism and gay rights seem to have been given a fresh breath, one that blew embers into flame.

Joining the big picture

Television was firmly established as a universal demotic medium. Its conscience prompted it to be as inclusive as it dared – “diversity” was born. Mind Your Language and Love Thy Neighbour were written to feature Asian, diverse immigrant and West Indian characters. It doesn’t matter now that the programmes of the era, mostly situation comedies and the occasional drama featuring black men as crooks, suffered later from accusations of patronisation, “stereotyping” and racist subtexts. Presence was all.

The battalions of political correctness had not yet laid siege to the public conscience and the writers and producers of these series certainly saw themselves as liberal pioneers of broadcasting. The writers may have misjudged the mood and reviewed today three or four decades later, their unfamiliarity with the cultures and idiom they sought to dramatise is ludicrously evident. Norman Beaton, working on Desmond’s in the nineties told me he had to rewrite the lines for himself and other black actors – sometimes on the set.

Probably the true breakthrough in television’s dramatic presentation of the new communities came with BBC Pebble Mill’s Empire Road series, written by Guyanese playwright Michael Abensetts and produced by the team of David Rose and Peter Ansorge. It was “comedy” only in the sense that the word applies to Shakespeare’s work, an exploration of stances and attitudes rather than a gag-fest. The drama kept itself refreshingly free of burning race issues. Not so the programmes that were at the same time, with classically liberal intent invading ITV. There was London Television Weekend’s (prop. John Birt) Skin which featured in each episode a problem occasioned by race: housing, education, employment, public services, police attitudes etc. This “etc” is statistically circular. Once they had done housing, education, employment, police attitudes, public services, they had to start again and do housing, education…. the “mission to complain” became “race” TV’s mainstay.

So the question being asked was: “What can TV do for racial minorities?” but not yet “What can racial minorities do for TV?” The worry of “hideously white” had not become insistent. The first question was now being answered in one obvious way – put the protest of blacks onto the screen. Protest is one democratic way of winning rights and gaining positions, but is it the substance of TV? For one thing it gets repetitive and boring and begins to sound, as these programmes complaining about racism and asking for concessions inevitably did, like begging in a bullying voice, a bluff that Britain has invariably called through its colonial history.

The new platform

The pressures of British liberalism brought about the conception and reality of Channel 4. There were fresh interests rampant in the population and these would now be represented on a new televisual platform. The channel was conceived under a Labour administration but sanctioned and implemented during Thatcher’s tenure. Good Marxist theoretician that she was, she and her advisors who gave it their executive imprimatur realised that Channel 4, while espousing all manner of causes and points of view inimical to Conservatism, would bring the small entrepreneur into the broadcasting market, challenging the large monopolies of the BBC and ITV. It would be the generation of the independent TV producers, the generation of a wedge of small business, hiring and firing its employees, into the union-dominated world of BBC and ITV. The likes of Tariq Ali and Darcus Howe, radical in tooth and claw, would become owners of TV production companies that hired and fired as the processes of commissioning and production demanded.

Ideologically Channel 4 was, by parliamentary remit, the representative of minority interests. Jeremy Isaacs, its first supremo, appointed Sue Woodford, a Trinidadian Brit and an experienced programme producer as the channel’s first multicultural commissioning editor. Woodford’s programming was revolutionary. She ditched the mission to complain and ran on the channel, among a diversity of offerings, one West Indian and one Asian magazine show, a black arts showcase programme and then a situation comedy called No Problem, co-written by veteran Trinidadian playwright Mustafa Matura and myself. The brief to the writers was clear – a situation comedy makes people laugh. It featured five Caribbean siblings living in a house in Willesden, London, each with their own conceits and relationships to Britain. It was funny, it worked, it got audience figures and significantly it was a huge hit amongst the youth of West Indian origin.

In the wake of the series’ success I was invited by a Mr Sivanandan, who was the boss the Institute of Race Relations, to speak to an audience about my TV comedy. I went. Sivanadan was chairing the event. He introduced me, virtually saying that this was a trial of my consciousness. “No Problem is a problem!” he thundered, striking the table. I quickly gathered it was a set up. I was the golden-calf-worshipper of triviality in a Mosaic congregation of anti-racist righteousness. It was a parting of many ways. The sub-text of some of the protest and anti-racist movements of the sixties and seventies was a sort of revolutionary wishful thinking. The Black Panthers in America professed that the demand for rights for black people was tantamount to a demand for a revolution in the United States and black people were the vanguard of that revolution. It was the British counterpart of that argument that led Mr Sivanandan to reject the idea of a black situation comedy on TV. There was no time for frivolity. My own experience, beginning perhaps with the same premise of radical and revolutionary thinking, had brought me to a contrary persuasion.

I had been an active member of a succession of immigrant radical groups one of which ran an agitational newspaper called Freedom News. One of the inspirations of the group was the Trinidadian Marxist philosopher C L R James who addressed a meeting of the group on the content of this pamphleteering newssheet. He was of the opinion that an agitational sheet such as ours should first and foremost speak of the experience of its members. “What is it you do for a living?” was his question to the audience. “I drive a London Transport bus,” was the first answer. “Then write about what happens in the garage, your experience in the streets, in the trade union, with the public etc.” Turning eventually to me, a schoolteacher at the time, he said I should write about the conflicts and dramas of the school and the classroom. Surely I had stories to tell.

I did. I wrote these stories week after week and after a few editions was visited by a young man in a pin-striped suit asking for me in the school playground. He wasn’t from the police as the pupils whom he accosted thought, but was an editor at the publishing house Macmillan. He said he had found out that I was the writer of the school “stories” in Freedom News and that he would like to commission me to write a book of them. He said, memorably, that the audience for “multicultural fiction” existed before the books did. I accepted the commission and wrote my first published book and then a second and a third. It was after the third book that Peter Ansorge, the producer of Empire Road at BBC’s Pebble Mill approached me and asked if I would transform a set of my stories into TV plays. The series was written and directed by various directors with “radical” credentials among them John McGrath, Jon Amiel and Horace Ove.

In 1982, a year after the series was broadcast Channel 4 was born. What was its first multicultural editor determined to do? If the Reithian formula of educating and entertaining was generally true for broadcasting then it was true for this specialist programming. Under Sue Woodford the mission to complain was subverted. There were two clear strategic objectives which emerged from Channel 4. More people from the ethnic communities should be making programmes, serving an apprenticeship if necessary. There were, inevitably headcounts of the number of ethnic faces appeared on-screen as newsreaders, reporters, presenters or actors. A fair volume of programming of diverse sorts would ensure or at least begin the assimilation of the new communities into the nation’s primary instrument or mirror of self-awareness.

The recruitment of writers, directors, producers and actors from the ethnic minorities assured not only the attrition of hideous whiteness, but perhaps more importantly a familiarity with the culture, the communities and the issues which brought authority and authenticity to the programmes. The problem remains that the word (adjective of “white”, adverb qualifying “appears”?) “hideously” is not amenable to statistical exactitude. If the new black and brown communities of Britain constitute four per cent of the population, does it mean that there should be only one ethnic newscaster out of every 25? Or one black hero or heroine in 25 series of detective or hospital stories? Wouldn’t a strictly statistically representative approach lead to a mass cull of “diverse” persons from the BBC’s output? And one could ask why aren’t the successive director-generals crying out for more Polish representation on screen now that there is a considerable Polish working population in the UK?

The impulse to “diversity” and multiculturalism began with the project of assimilation. It certainly included giving chicken tikka masala the respect it deserves, but was never intended to inculcate a tolerance, for instance, of female genital mutilation, religiously sanctioned polygamy or stoning adulteresses to death on the grounds that these were part of the “culture” of some new communities. “Multiculture” is simply an acceptable, liberal term for an inclusive, wide, but judgemental monoculture.

Leave positive imaging to Saatchi and Charles Saatchi (or maybe not)

That doesn’t preclude documentaries which tell the truth about the practice of female genital mutilation in the name of religion or culture. The idea that the lives or culture of the new communities should be portrayed by television in “positive images” is another untenable tenet of liberal thought. It is undoubtedly the first idea that occurs to BBC heads of this or that when they make decisions about “diversity”. The proposition is untenable because television is not an advertising agency for blacks and any attempt to make it so demeans the intelligence of viewers. There may be a case for the presentation of role models, but there is also a case for inculcating a respect for reality.

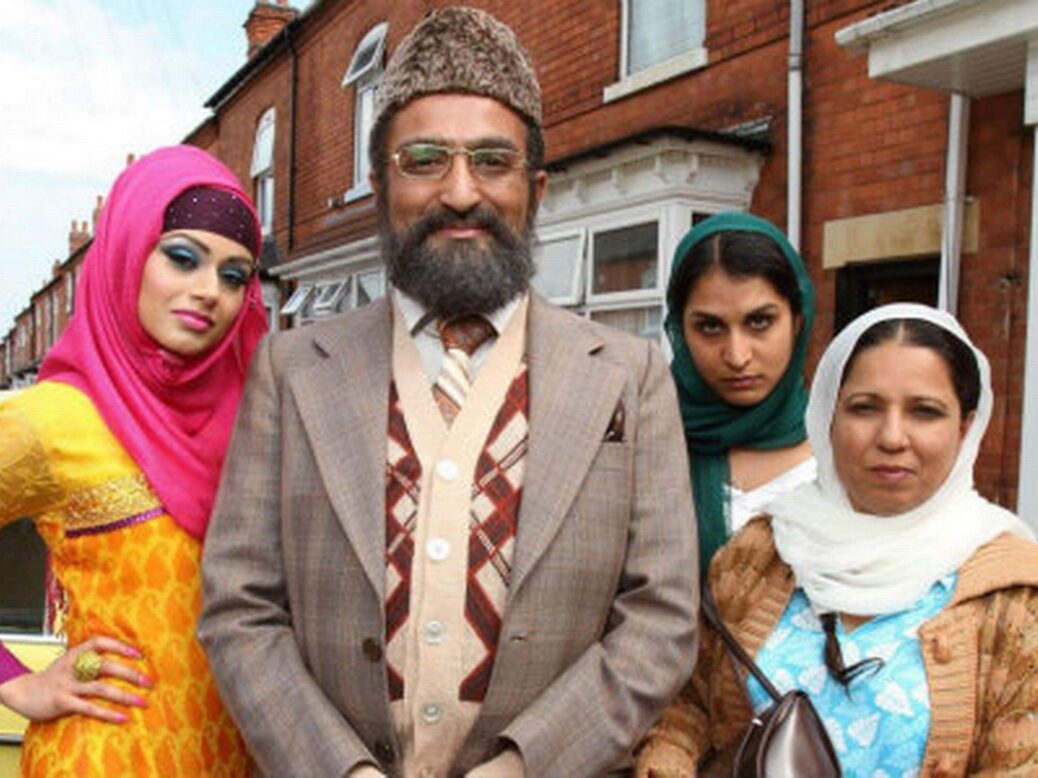

A snapshot of contemporary BBC programmes demonstrates a determination to remedy the hideousness of white reportage. There are “diversity” (I like being called “a diverse” rather than an Indian person) news presenters and reporters all over the screen. There are comedy appearances which can be seen as concessional or even abused for being negatively stereotypical – all part of the fun. The Citizen Khan episodes are a clumsy attempt to cock a snook at positive image and non-stereotypical imagery. Then there are plausible black detectives who always get their man or woman and demonstrate compassion for the criminal compelled by his or her fate to unspeakable deeds. Again high marks out of ten, even though the principle could lead to unlikely, say, brain surgeons or black Winston Churchills thrown in.

The main failure of the Kafkaesque structure of the BBC in which looking warily over one’s shoulder is a necessary survival instinct, is it prevents editors and commissioners from making the creative associations between “non-white” and the diverse and vital cultures of the screen. “Diversity” becomes not a creative but a policing venture.

A brief story featuring the journey towards diversity: I was, from the mid-Eighties for several years, the second appointed commissioning editor for multicultural programmes at Channel 4. Part of the brief I had formulated or accepted was to recruit or encourage a brace of independent production companies with black and Asian owners, producers, directors researchers and so on. Some of the smaller of these companies made a series of investigative, observational and polemically necessary documentaries for the channel. As some of the people making these docs were fairly or absolutely new to the medium, I appointed Bernard Clark, an experienced (white) TV hand to be an executive producer of the series which we called The Black Bag.

When the series was about to be transmitted an Asian journalist previewed it and approached me for an interview. He asked a few routine questions and then came out with what seemed a carefully rehearsed question: “Since you have put a white man in charge of a collection of ethnic producers, what would you say if someone accused you of acting like a typical slave-dealer or a colonial governor?” These parallels hadn’t occurred to me but what did immediately come to mind was a multicultural phrase which I had absorbed from my college days in Poona. I replied: ‘I’d say “kiss my cock and call me Charlie!”’ He shut his notebook and stormed out of my office.

Two hours later I was summoned to the Channel Controller’s office to be confronted by two of my bosses, Liz Forgan and John Willis. “Did you just tell a journalist to kiss your cock and call you Charlie?” asked Liz Forgan with a poker face. I quoted the journalist’s question and attempted to justify my answer which I repeated. Neither Liz nor John could now keep a straight face. John nearly fell off his chair. A triumph I thought for multicultural expression.

Conclusion: BBC now “hideously corporate”

When Margaret Thatcher, the Lenin of the lower middle-class British revolution, and her government set up Channel 4, they structured it to stimulate the existence of small independent production companies. The small companies born out of this venture, some of which, in the early competition that Channel 4 offered the BBC, were commissioned by the Beeb, have all but gone out of business or been absorbed in larger companies.

The BBC never had in its remit the encouragement of small independent companies and very many ethnic producers took employment with larger monoliths or went out of business. As a result the commissioning landscape, certainly that of the BBC, is now hideously corporate.

Farrukh Dhondy is a novelist, screenwriter and the former commissioning editor for multicultural programming at Channel Four